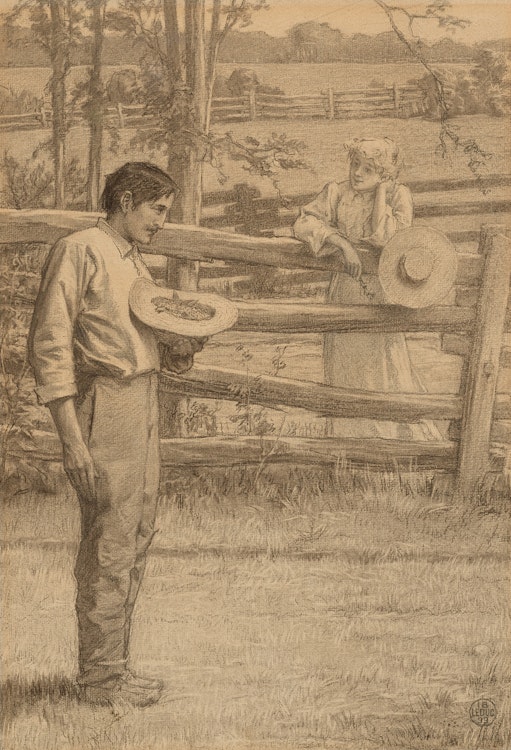

The Meeting of Fernande and Claude (La rencontre de Fernande et de Claude), 1899 by Ozias Leduc

Ozias Leduc

The Meeting of Fernande and Claude (La rencontre de Fernande et de Claude), 1899

charcoal

monogrammed and dated 1899 in a stamp lower right

23.5 x 17.5 ins ( 59.7 x 44.5 cms ) ( sheet )

Auction Estimate: $2,500.00 - $3,500.00

Price Realized $2,400.00

Sale date: December 6th 2023

Luc Choquette et Pauline de Montgaillard, 1943

Luc Choquette

Walter Klinkhoff Gallery, Montreal

Acquired by the present Private Collection, 2004

“Ozias Leduc: An Art of Love and Reverie”, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; travelling to Musée du Québec, Québec City; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 22 February 1996‒15 January 1997, no. 95 as “Mais elle, ceci l'amusait ce grand garçon si brun...”

Laurier Lacroix, “Ozias Leduc: An Art of Love and Reverie”, Montreal, 1996, no. 95, reproduced page 130

Laurier Lacroix, ‘Deux ‘Canayens' à la recherche de la nouveauté : Claude Paysan (1899) du Dr Ernest Choquette par Ozias Leduc’, “À la rencontre des régionalismes artistiques et littéraires Le contexte québécois 1830‒1960”, Québec, 2014, pages 237‒258

The passage reads: “But her, as a true daughter of Eve, she found this amusing, this tall young man with dark brown hair, who appeared so shy in her presence and she kept talking to him...”. The author dates this scene to August, during the cherry season, and the artist positions the two figures in different physical and psychological spaces. The barrier stands for social distancing.

A fatherless Claude watches over his old mother while caring for the family farm. He loves Fernande, a town-dweller who stays in the countryside during the summer. Everything separates these two individuals: their family background, their culture, and especially the fact that Fernande is suffering from an incurable and deadly disease. At her death, desperate, Claude drowns himself, leaving his mother forsaken. The illustrated passage relates, however, a happy moment, that of the meeting between these two young people when Claude stumbles on Fernande when returning from the fields.

The artwork is part of a set of fifteen drawings reproduced in the novel, of which many are kept in public collections (National Gallery of Canada, Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec). This novel is one of the very first illustrated books by a French Canadian author. The story takes place in the village of Saint-Hilaire, and, for the first time, inspired by the author, Leduc uses its living environment as a subject matter. Here, we find a country road bordered by imposing pole fences delineating the fields. The vertical image is structured by a succession of fences, which deal with the organization of strips of farmland in the Quebec countryside.

Leduc has positioned Claude prominently in the foreground, thus highlighting the emotions of the lost young man beholding the beauty and the aura of the young girl. Throughout the novel, the hero appears as an introverted individual who will not successfully bridge the gap between Fernande and himself. The precise contours of the drawing delineate, in fact, the distinct positions of the two protagonists.

The charcoal drawing technique is masterful and the artist has paid significant attention to details, as evidenced by Claude’s clothing. He used the stump to mark the volumes and the eraser as a drawing method, in the grass, for example, and to accentuate the lighting in the subject.

Leduc attached importance to these drawings, which he kept for a long time. This one and at least two others were hanging in the Saint- Hilaire studio before being acquired in 1943 by Luc Choquette, the son of the novel’s author and his wife.

We extend our thanks to Laurier Lacroix, C.M., art historian, for researching this artwork and for contributing the preceding essay.

Share this item with your friends

Ozias Leduc

(1864 - 1955) RCA

Born at St. Hilaire, Quebec, he began to paint with Luigi Cappello in the decoration of Saint-Pail l'Ermite church. Cappello was an Italian painter who had done church decoration for many churches in Quebec. Later Leduc became associated with Adolphe rho in the decoration of the church of Yamachiche, including the painting of a copy of Raphael's “Transfiguration” and, a picture entitled “Bapteme du Christ” destined for the church of Saint-Jean-in-Montana, Jerusalem. Although this last painting was done by Leduc it was a commission given to Rho and done in his shops and therefore signed by Rho. An engraving after this painting was made but was not a faithful reproduction of the original work.

Most of Leduc's art training was acquired through the process of observation and self teaching. By the age of twenty-three, Leduc was producing beautiful still life studies bathes in warm candle light or from the light of a distant window. A painting from this period entitled “Les Trois Pommes” was given to Paul-Emile Borduas by the artist as Borduas was his assistant for many years in the decoration of churches and a life long friend.

In 1892, Leduc entered a painting in the Art Association of Montreal annual show and won a prize for the best work done by an artist under thirty. It was during this year and the next that he did decorations for the Joliette Cathedral.

In 1897 he sailed for France in the company of Suzor-Côté. There Leduc became considerably impressed with three lessor known Impressionists, René Ménard, Alfons Mucha and Le Sidaner also Maurice Denis in religious art especially.

He returned to Canada after eight months and set to work on decorations for the church at St. Hilaire. Nothing the effect of the Impressionists on Leduc's work, Jean René Ostiguy explained, “But the techniques of French impressionism, when transplanted to Saint-Hilaire, bore a very different fruit. For Leduc they were the means for weaving reveries and for expressing the tenderness which he felt before all life and all created things. His drawing, the care he devoted to his surfaces, show his early influences. But the real difference came in the handling of light. From him light was the symbol of another, an ideal world. He saw nature in the light of his dreams, and there is good reason for associating him with the surrealist tendency which is sometimes to be found in Renaissance painting. Because of his development took this unusual course, Leduc's paintings are not modern in the ordinary sense. Yet in a deeper sense they are completely contemporary in spirit. His insistence on the poetic basis of art and his strongly personal manner of expression are qualities which contemporary painters revere and seek as essential elements in their work.”

Also commenting on the artists Gilles Corbeil noted, “The extraordinary care which Ozias Leduc lavished on his paintings is almost unbelievable. He seems at every moment to have been conscious of some moral responsibility for the way he treated his canvases and handled his brush and his colours. Nothing was left undone; no care was too great. Everything which went into the making of a picture, from the preparation of the stretcher for the canvas, was the work of his own hands. One begins to wonder what brush could have been soft enough, what palette smooth enough, to have been employed in the creation of such exquisite paintings. But the really touching thing about Leduc is the tenderness, even sanctity, which seems to govern all his work. For him, painting was never merely a manual craft but a flowering character, an act of grace. For him the paint itself seemed sensitive, and perhaps it was for fear of violating it that he treated it with such greatness.” Corbeil went on to explain that throughout his life Leduc painted only some twenty still life studies of simple everyday things such as a candlestick, a loaf of bread, apples, a book, violin, a knife or spoon beside a bowl but he never painted flowers in these studies. Corbeil equated Leduc's treatment of objects with that os jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin, the Frech master who also endowed his still lifes with a certain dignity although Chardin was a more worldly and sophisticated painter. Corbeil thought too, that the enchanted austerity of Leduc's paintings might be better compares to the Dutch still life painter Willem Claesz Heda. Heda, however, unlike Leduc included flowers in his compositions but he achieved that aura of silence that Leduc always created in his still lifes.

During the earlier part of his life, Leduc did a number of portraits as well as landscapes. He made his living mainly from church decorations of which he did more than one hundred and fifty paintings for about twenty-eight cathedrals, churches, or chapels. His portraits and other works were done with oil on paper, oil on cardboard, oil on canvas. He did a number of oil on cardboard paintings. He kept track of his pencil drawings which were at times done on the back of envelopes and sometimes numbered.

In 1916 he was elected Associate of the Royal Canadian Academy and in 1938 received the degree of Doctor Hornoris Causa from the University of Montreal. In addition, he illustrated many novels, poetry books and anthologies.

There have been three important showings of Leduc's work as follows: at the St. Sulpice Library, Montreal in 1916; a retrospective exhibition at the Lycée Pierre Corneille, Montreal in 1954 and a retrospective exhibition organized by Jean René Ostiguy for the National Gallery of Canada which included forty-one oil, charcoal, and coloured crayon drawings and paintings. Leduc was still active at the age of ninety, overseeing the work for the decoration of the church at Almaville-en-Bas near Shawinigan Falls. He died at St. Hyacinthe aged ninety-one. He is represented in the following public collections: Museum of the Province of Quebec; The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and the National Gallery of Canada.

Source: "A Dictionary of Canadian Artists, Volume I: A-F", compiled by Colin S. MacDonald, Canadian Paperbacks Publishing Ltd, Ottawa, 1977