Nature morte au livre (Crépuscule de Michel-Ange) by Ozias Leduc

Ozias Leduc

Nature morte au livre (Crépuscule de Michel-Ange)

oil on canvas

signed and dated 1940 lower right

16 x 24 ins ( 40.6 x 61 cms )

Auction Estimate: $50,000.00 - $70,000.00

Price Realized $45,600.00

Sale date: December 1st 2022

Commissioned by Frederick and Florence Bindoff, Montreal 1940

Galerie Dominion, Montreal, 1955

J.H. Laframboise et Cie, Montreal, 1955

Maurice Duplessis, 1955

Galerie Valentin, Montreal

Private Collection, Toronto

“Exposition d’Edmond Dyonnet, Ozias Leduc, Joseph Saint-Charles, Elzéar Soucy”, Musée de la Province du Québec, décembre 1945-janvier 1946, no. 26 “Nature morte”

“Laboratoire de l'intime: les natures mortes d'Ozias Leduc / Confidential Experiments: The Still Lifes of Ozias Leduc”, Musée d'art de Joliette, 3 June - 17 September 2017, no.10

“Collectors’ Treasures II / Trésors des collectionneurs II”, Galerie Eric Klinkhoff, Montreal, 24 October-7 november, 2020, no. 20

Jean-René Ostiguy, “Ozias Leduc: Peinture symboliste et religieuse / Ozias Leduc: Symbolist and Religious Painting”, Ottawa, Galerie nationale du Canada, 1974, p.192, reproduced

Arlene Gehmacher, in “Ozias Leduc: Une oeuvre d'amour et de rêve / Ozias Leduc: An Art of Love and Reverie”, Musée du Québec & Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, 1996, pp. 244-247, 275, 307, reproduced p. 297

Laurier Lacroix, “Laboratoire de l'intime: les natures mortes d'Ozias Leduc / Confidential Experiments: The Still Lifes of Ozias Leduc”, Musée d'art de Joliette, 2017, pp. 26-27, 31-32, reproduced p. 27

In 1940, the artist took the opportunity to return to this genre when he accepted a commission from his good friends Frederick and Florence Bindoff. He had already painted their portrait and the couple owned some of Leduc’s paintings.

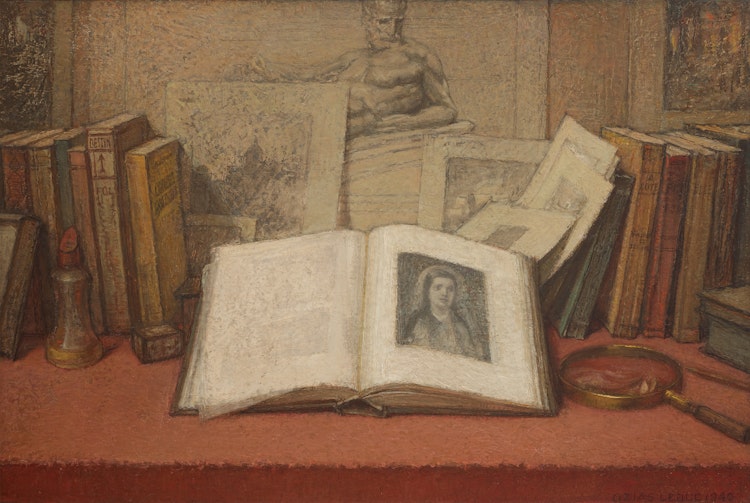

At age 76, Leduc revisited this subject, which has been studied extensively and been the object of many masterpieces, offering his own meditation on it. The composition displays an arrangement of books, illustrated sheets of paper and a reproduction of Michelangelo’s

sculpture “Dusk”, which overlooks the tomb of the de Medicis in Florence, and dominates the arrangement of assembled objects. By referencing a famous allegory of old age, the painter imbues the artwork with a reflection on his own state and the enduring quality of creation.

In spite of his age, Leduc presents a celebration of life and art. For the painter, life is synonymous with research, study and beauty. Leduc evokes this expression by representing books, some of which reveal their author or French title: DESTIN, A. COTE, VINCENT LE JEUNE, FOI, ELLE. They are enigmatic inscriptions, with words heavy with meaning offering hints, like a mystery to be solved. Could the magnifying glass and jar of glue be used to expand and assemble these fragments, and provide meaning and context in order to make sense of them? These tools are presented as various means at our disposal to understand the world.

Similarly, the grouping of several images ends up hiding the subject matter rather than displaying it. In the symbolic universe of Leduc, creation is a world to explore. Unobstructed, the portrait of a young woman with a halo is clearly visible in the center of an open illustrated book. She will serve as our guide: a symbol of youth in dialogue with old age, its antithesis.

The artist’s technique and application of a thick, almost granular pigment remind the viewer that the portrait is a painted image. Brushstrokes outline each plane and form, adding texture to the dense, veiled universe. We are not faced with a “trompe‒l’œil” as in Leduc’s early canvases, but rather a painting that is both solemn and intangible, a celebration of the many possibilities of his art.

We extend our thanks to Laurier Lacroix, C.M., art historian, for contributing the preceding essay.

Ozias Leduc s’est fait connaître au début de sa carrière, dans les années 1890, comme peintre de natures mortes. Il en expose régulièrement, remporte des prix, attire l’attention de la critique par le biais de toiles qui racontent la vie silencieuse des objets de son atelier : matériel d’artiste, livres, reproductions d’œuvres d’art. Puis, il les intègre dans ses scènes de genre montrant ses modèles avec ses biens qui l’entourent au quotidien.

En 1940, l’occasion lui est fournie de revenir à ce genre afin de répondre à une commande de ses grands amis, Frederick et Florence Bindoff. L’artiste a déjà peint leur portrait et ils sont les propriétaires de quelques-uns de ses tableaux.

À 76 ans, Leduc traite de nouveau d’un sujet qui a été l’objet de tant de recherche et de chefs-d’œuvre et il en propose une méditation adaptée à sa situation. La composition s’organise autour de quelques livres, de feuilles illustrées et de la reproduction de la sculpture de Michel-Ange, “Crépuscule”, qui surplombe le tombeau de des Médicis à Florence et domine la disposition des pièces réunies. Par la citation de cette célèbre allégorie de la vieillesse, le peintre inscrit une réflexion sur son état et la pérennité de la création.

En dépit de son âge, Leduc propose une célébration de la vie et de l’art. Pour l’artiste, la vie est synonyme de recherche, d’étude et de beauté. Il en réunit l’expression au moyen de livres dont quelques-uns montrent leur titre ou leur auteur : DESTIN, A. COTE, VINCENT LE JEUNE, FOI, ELLE. Inscriptions énigmatiques, où des mots lourds de sens propose un rebus, comme un mystère à résoudre. Une loupe et un pot de colle bien en évidence peuvent-ils servir pour assembler ces fragments, les approfondir, leur donner du sens et mieux les comprendre ? Ces outils se présentent comme autant de moyens dans notre compréhension du monde.

De même, les images réunies dissimulent leur sujet plutôt que l’affichent. Dans l’univers symbolique de Leduc, la création est un monde à explorer. Seule, au centre d’un livre illustré ouvert, le portrait d’une jeune femme auréolée est bien visible. Elle sera notre guide. L’illustration de la jeunesse peut entrer en dialogue avec le relief de l’âge avancé.

La technique utilisée par l’artiste, une matière picturale épaisse, comme granuleuse, insiste sur le fait qu’il s’agit bien d’une représentation peinte où le pinceau cerne les plans et les formes, donne une texture à cet univers voilé, mais dense. Nous ne sommes pas face un trompe-l’œil comme dans ses premières toiles, mais devant une peinture à la fois grave et impalpable, une célébration de toutes les possibilités de son art.

Nous désirons remercier l’historien d’art Laurier Lacroix pour son aide dans la recherche de cette œuvre et sa contribution à l’essai précédent.

Share this item with your friends

Ozias Leduc

(1864 - 1955) RCA

Born at St. Hilaire, Quebec, he began to paint with Luigi Cappello in the decoration of Saint-Pail l'Ermite church. Cappello was an Italian painter who had done church decoration for many churches in Quebec. Later Leduc became associated with Adolphe rho in the decoration of the church of Yamachiche, including the painting of a copy of Raphael's “Transfiguration” and, a picture entitled “Bapteme du Christ” destined for the church of Saint-Jean-in-Montana, Jerusalem. Although this last painting was done by Leduc it was a commission given to Rho and done in his shops and therefore signed by Rho. An engraving after this painting was made but was not a faithful reproduction of the original work.

Most of Leduc's art training was acquired through the process of observation and self teaching. By the age of twenty-three, Leduc was producing beautiful still life studies bathes in warm candle light or from the light of a distant window. A painting from this period entitled “Les Trois Pommes” was given to Paul-Emile Borduas by the artist as Borduas was his assistant for many years in the decoration of churches and a life long friend.

In 1892, Leduc entered a painting in the Art Association of Montreal annual show and won a prize for the best work done by an artist under thirty. It was during this year and the next that he did decorations for the Joliette Cathedral.

In 1897 he sailed for France in the company of Suzor-Côté. There Leduc became considerably impressed with three lessor known Impressionists, René Ménard, Alfons Mucha and Le Sidaner also Maurice Denis in religious art especially.

He returned to Canada after eight months and set to work on decorations for the church at St. Hilaire. Nothing the effect of the Impressionists on Leduc's work, Jean René Ostiguy explained, “But the techniques of French impressionism, when transplanted to Saint-Hilaire, bore a very different fruit. For Leduc they were the means for weaving reveries and for expressing the tenderness which he felt before all life and all created things. His drawing, the care he devoted to his surfaces, show his early influences. But the real difference came in the handling of light. From him light was the symbol of another, an ideal world. He saw nature in the light of his dreams, and there is good reason for associating him with the surrealist tendency which is sometimes to be found in Renaissance painting. Because of his development took this unusual course, Leduc's paintings are not modern in the ordinary sense. Yet in a deeper sense they are completely contemporary in spirit. His insistence on the poetic basis of art and his strongly personal manner of expression are qualities which contemporary painters revere and seek as essential elements in their work.”

Also commenting on the artists Gilles Corbeil noted, “The extraordinary care which Ozias Leduc lavished on his paintings is almost unbelievable. He seems at every moment to have been conscious of some moral responsibility for the way he treated his canvases and handled his brush and his colours. Nothing was left undone; no care was too great. Everything which went into the making of a picture, from the preparation of the stretcher for the canvas, was the work of his own hands. One begins to wonder what brush could have been soft enough, what palette smooth enough, to have been employed in the creation of such exquisite paintings. But the really touching thing about Leduc is the tenderness, even sanctity, which seems to govern all his work. For him, painting was never merely a manual craft but a flowering character, an act of grace. For him the paint itself seemed sensitive, and perhaps it was for fear of violating it that he treated it with such greatness.” Corbeil went on to explain that throughout his life Leduc painted only some twenty still life studies of simple everyday things such as a candlestick, a loaf of bread, apples, a book, violin, a knife or spoon beside a bowl but he never painted flowers in these studies. Corbeil equated Leduc's treatment of objects with that os jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin, the Frech master who also endowed his still lifes with a certain dignity although Chardin was a more worldly and sophisticated painter. Corbeil thought too, that the enchanted austerity of Leduc's paintings might be better compares to the Dutch still life painter Willem Claesz Heda. Heda, however, unlike Leduc included flowers in his compositions but he achieved that aura of silence that Leduc always created in his still lifes.

During the earlier part of his life, Leduc did a number of portraits as well as landscapes. He made his living mainly from church decorations of which he did more than one hundred and fifty paintings for about twenty-eight cathedrals, churches, or chapels. His portraits and other works were done with oil on paper, oil on cardboard, oil on canvas. He did a number of oil on cardboard paintings. He kept track of his pencil drawings which were at times done on the back of envelopes and sometimes numbered.

In 1916 he was elected Associate of the Royal Canadian Academy and in 1938 received the degree of Doctor Hornoris Causa from the University of Montreal. In addition, he illustrated many novels, poetry books and anthologies.

There have been three important showings of Leduc's work as follows: at the St. Sulpice Library, Montreal in 1916; a retrospective exhibition at the Lycée Pierre Corneille, Montreal in 1954 and a retrospective exhibition organized by Jean René Ostiguy for the National Gallery of Canada which included forty-one oil, charcoal, and coloured crayon drawings and paintings. Leduc was still active at the age of ninety, overseeing the work for the decoration of the church at Almaville-en-Bas near Shawinigan Falls. He died at St. Hyacinthe aged ninety-one. He is represented in the following public collections: Museum of the Province of Quebec; The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and the National Gallery of Canada.

Source: "A Dictionary of Canadian Artists, Volume I: A-F", compiled by Colin S. MacDonald, Canadian Paperbacks Publishing Ltd, Ottawa, 1977