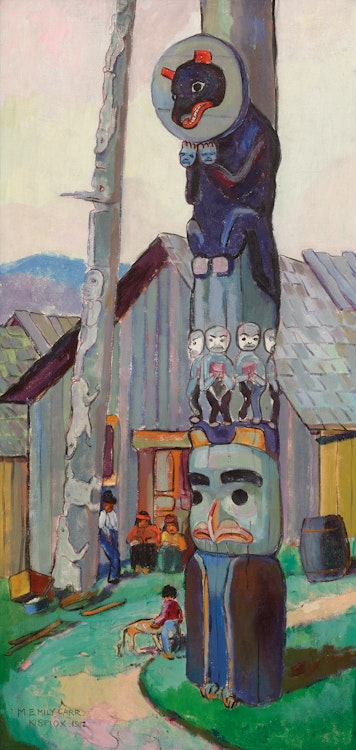

The Totem of the Bear and the Moon by Emily Carr

Emily Carr

The Totem of the Bear and the Moon

oil on canvas

signed “M. Emily Carr”, dated 1912 and inscribed “Kispiox” lower left

37 x 17.75 ins ( 94 x 45.1 cms )

Auction Estimate: $2,000,000.00 - $3,000,000.00

Price Realized $3,120,000.00

Sale date: December 1st 2022

Acquired from the artist by Marius Barbeau, June 1928

McCready Gallery, Toronto 1970

Acquired by the present Private Collection, 1970

Possibly “Paintings of Indian Totem Poles and Indian Life by Emily Carr”, Dominion Hall, Vancouver, from 16 April 1913

“Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art Native and Modern”, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; travelling to the Art Gallery of Toronto; Art Association of Montreal, 3 December 1927‒22 April 1928, no. 13 as “Kispayaks Totem Poles”

“Paintings in Ottawa Collections”, National Gallery Association, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 10 April‒6 May 1959, as “Totem”

“Collector’s Canada: Selections from a Toronto Private Collection”, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; travelling to Musée du Québec, Quebec City; Vancouver Art Gallery; Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon, 14 May 1988‒7 May 1989, no. 86

“To the Totem Forests: Emily Carr and Contemporaries Interpret Coastal Villages”, Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 5 August‒31 October 1999, hors catalogue, McMichael Canadian Art Collection only

“Emily Carr (1871‒1945): Retrospective Exhibition”, Galerie Walter Klinkhoff, Montreal, September 2002, no. 14

“Emily Carr: New Perspectives on a Canadian Icon”, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; travelling to the Vancouver Art Gallery; Art Gallery of Ontario; Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; Glenbow Museum, Calgary, 2 June 2006‒26 January 2008, no. 37

“Embracing Canada: Landscapes from Krieghoff to the Group of Seven”, Vancouver Art Gallery; travelling to the Glenbow Museum, Calgary; Art Gallery of Hamilton, 29 October 2015‒25 September 2016 Highlights from “Embracing Canada”, Galerie Eric Klinkhoff, Montreal, 22 October‒5 November 2016, no. 13

“Pop Up Museum”, Canadian Friends of the Israel Museum, 9 August 2017

“Emily Carr: Fresh Seeing”, Audain Art Museum, Whistler, British Columbia; travelling to the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton, 21 September 2019‒31 May 2020, no. 95

Marius Barbeau, “The Downfall of Temlaham”, Toronto, 1928, reproduced opposite page 206 as “The Totem Pole of the Bear and the Moon at Kispayaks‒the ‘Hiding Place’” (and in facsimile edition, Edmonton, 1973)

Marius Barbeau, “Totem Poles of the Gitksan, Upper Skeena River, British Columbia”, Ottawa, 1929, pages 58‒59, 84‒85, plate IX, figure 4, plate XV, figure 3 (and in facsimile edition, Ottawa, 1973)

‘Visit the land of the mystic totem ... magnificent British Columbia’, “Canadian National Railways Magazine”, vol. 17, no. 2 (Feb. 1931) reproduced on back cover as “The Totem Pole of the Bear and the Moon, Kispayaks”

Albert H. Robson, “Canadian Landscape Painters”, Toronto, 1932, reproduced page 187 as “The Totem of the Bear and the Moon”

Marius Barbeau, “Totem Poles of the Gitskan, Upper Skeena River, British Columbia”, Ottawa, 1929, pages 58‒59, 226‒227, pl. IX, fig. 4, and pages 84‒85 as “Grizzly‒of–the‒Sun”, 238‒239, pl. XV, fig. 3 (facsimile edition Ottawa, 1973)

Edythe Hembroff‒Schleicher, “Emily Carr: The Untold Story”, Saanichton, B.C., 1978, pages 117‒119, reproduced page 106 as “The Bear and Moon Totem”

Maria Tippett, “Emily Carr, A Biography”, Toronto, 1979, pages 153, 293 note 49

Paula Blanchard, “The Life of Emily Carr”, Vancouver/Toronto, 1987, pages 183‒184

Dennis Reid, “Collector’s Canada: Selections from a Toronto Private Collection”, Toronto, 1988, no. 86, pages 6, 78, reproduced page 11

Ann Morrison, “Canadian Art and Cultural Appropriation: Emily Carr and the 1927 Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art – Native and Modern” (M.A. thesis, University of British Columbia, 1991) pages 81‒82, 88, reproduced page 146, fig. 8

Gerta Moray, “Northwest Coast Native Culture and the Early Indian Paintings of Emily Carr, 1899‒1913” (PhD. Dissertation, University of Toronto, 1993), Vol. I: pages 296‒298, 387‒388; Vol. II: page 33, illustration F.3, F.3/2, F.3/3

Laurence Nowry, “Man of Mana: Marius Barbeau”, Toronto, 1995, page 281

Sandra Dyck, ‘These Things Are Our Totem’: “Marius Barbeau and the Indigenization of Canadian Art and Culture in the 1920s” (M.A. thesis in Canadian Art History, Carleton University, Ottawa, 1995), page 86

A. Prakash, ‘Emily Carr (1871‒1945) Un artiste du Nouveau Monde hors de l’ordinaire’, “MagazinArt”, 12:1 (Fall 1999), reproduced page 98

Susan Crean, “The Laughing One A Journey to Emily Carr”, Toronto, 2001, page 179

Galerie Walter Klinkhoff, “Emily Carr (1871-1945): Retrospective Exhibition”, Montreal, 2002, no. 14, reproduced page 2

Marcia Crosby, ‘T’emlax’am: An Ada’ox’, in “The Group of Seven in Western Canada”, Calgary/Toronto, 2002, reproduced page 90

“Canadian Art”, 19:3, Fall 2002, reproduced page 206

“Etcetera”, 11 September 2002, reproduced page 13

Susan Vreeland, “The Forest Lover”, Toronto, 2003, page 269

Emily Carr, ‘Lecture on Totems’, in Susan Crean, editor, “Opposite Contraries: The Unknown Journals of Emily Carr, and Other Writings”, Vancouver, 2003, pages 177‒203

Charles C. Hill, ‘Backgrounds in Canadian Art’, in “Emily Carr New Perspectives on a Canadian Icon”, Ottawa/Vancouver, 2006, pages 118‒119, 121, 290 notes 135, 299, reproduced page 144, plate 103

Gerta Moray, “Unsettling Encounters: First Nations Imagery in the Art of Emily Carr”, Vancouver/Seattle, 2006, pages 100‒102, 106‒107, 286, 362 notes 5 & 6, 363 notes 32, 35, page 368 note 47, page 186, plate 30, reproduced page 189, plate 31, as “Kispiox, The Totem of the Bear and Moon”

Leslie Dawn, “National Visions, National Blindness Canadian Art and Identities in the 1920s”, Vancouver, 2006, pages 286‒287

Sandra Dyck, ‘A Playground for Tourists from the East’, in Lynda Jessup, Andrew Nurse and Gordon E. Smith, editors, “Around and About Marius Barbeau: Modelling Twentieth‒Century Culture”, Gatineau, Quebec, 2008, page 318

Ian Thom, et al., “Embracing Canada: Landscapes from Krieghoff to the Group of Seven”, Vancouver/London, 2015, page 200, reproduced page 172

Galerie Eric Klinkhoff, “Highlights from ‘Embracing Canada’,”, Montreal, 2016, no. 13, reproduced

Kiriko Watanabe, ‘A Fresh Look at the Northwest Coast’, in “Emily Carr Fresh Seeing”, Whistler, 2019, pages 94‒95, reproduced pages 95 and 145 as “Kispiox, The Totem of the Bear and Moon”

As Gerta Moray has written in her major publication, “Unsettling Encounters First Nations Imagery in the Art of Emily Carr”, “The Gitxsan poles on the Skeena were stylistically and iconographically different from the Kwakwaka’wakw poles Carr already knew.... Almost all the poles were free‒standing memorial poles, raised in memory of a chief by his or her successor. In addition to animal, bird and other crest images, these poles illustrated legends associated with the hereditary lineages and their founders. ... Stylistically, Carr found Gitxsan poles difficult to render. They were much taller than the Kwakwaka’wakw poles and were placed in a row some distance in front of the houses with which each was associated. To frame a pole within her composition required a very tall, narrow format, which allowed for little interesting background. The figures on the poles were complex and varied.... Gitxsan carving is both more naturalistic and more restrained than that of the Kwakwaka’wakw or the Haida. The human form occurs frequently, and the motifs on the poles are arranged in a series of registers one above the other, often in a contrasting scale.”

One of the Gitxsan villages Carr visited in 1912 was Ans’pa yaxw (Kispiox), the furthest she travelled up the Skeena. There she painted a pole that she identified as “The Bear and Moon Totem”. Carr did paint watercolours on this trip, especially on Haida Gwai, and Gerta Moray argues that she took panels as well as paper to paint on in situ. Some watercolours were subsequently worked up into oil paintings, but no studies are known for this work on canvas, which was probably painted in her Vancouver studio.

In 1924 Marius Barbeau, ethnologist at the National Museum in Ottawa, catalogued the pole Carr painted entitling it “Grizzly Bear of the Sun”. When she gave her lecture in April 1913, Carr had recounted the legend of Nekt, a legend associated with certain families in Ans’pa yaxw and which someone must have narrated to her. It is not clear how Carr came to the identification of this pole as The Bear and Moon Totem. Perhaps she misunderstood what she had been told or merely made the identification on a visual basis.

In 1929 Barbeau identified the pole as belonging to the family of Gitludahl, having been erected in commemoration of a member of that family and carved by Tsugyet, (James Green) about 1900. Carr’s painting only includes the three lower figures on the pole: the Grizzly Bear with the sun around his neck, five small human figures termed “People‒around,” and the Owl. According to Barbeau, the Grizzly Bear of the Sun derives from a legend associated with the Gitludahl family. “The ancestors of Gitludahl were camping at Salmon‒creek (“Shegunya”), opposite the present‒day Kispayaks, and fishing salmon. A maiden in seclusion saw coming down Salmon‒creek the bear with a ‘sun collar” around its neck (“medeegem‒gyamk”), which her parents killed and gave her for her posterity to use as an emblem.”

At the left is another pole, not identified by Carr, but catalogued by Barbeau as a pole of the family of Ma’us and titled Frog‒pole. It was carved by Wawsemlarhae (Robison) between 1874 and 1884. Carr’s painting includes the Person‒of‒the‒smoke‒hole (“Gyoedem‒alaih”); the Frog or Tadpole (“Ranaa’o”) head downwards; the Woodpecker (“Semgyeek”); Man‒of‒the‒smoke‒hole repeated; and the Frogs‒ jammed‒up (“Meetsehl‒ranaa’o”), one looking down, one turned sideways and the third looking upwards. Barbeau understood the figures to be family crests.

A map of the location of the poles at Ans’pa yaxw illustrated in Moray’s thesis (vol. II, F.3) shows that the two poles were in fact in close proximity, though placed in front of their owners’ respective houses. The second pole is not seen in photographs of the Grizzly‒of‒the‒Sun pole taken in 1913 (Moray 2006, page 101 and “Emily Carr Fresh Seeing”, page 94). In Carr’s large canvas (private collection) of multiple poles at Ans’pa yaxw (Moray 2006, plate 30), the Frog‒pole is depicted at the left but the Grizzly‒of‒the‒Sun pole is not visible. A.Y. Jackson visited Ans’pa yaxw in 1926 and drew the Grizzly‒of‒the‒Sun pole (National Gallery of Canada, acc. no. 17471) but the Frog‒pole is not seen in his drawing. Carr twinned the two poles for pictorial effect and animated the composition by including the child and dog and observant villagers.

Carr recognized the potential documentary importance of her paintings of poles and villages and in November 1913 she tried to sell her “collection” to the Province of British Columbia for a planned Provincial Museum. “The object of my work is to get the totem poles in their own original settings,” she wrote. However, the tension between the documentary and pictorial in her paintings, and the onset of an economic recession, resulted in the rejection of the proposed purchase. She left Vancouver and moved back to Victoria and over the next fourteen years rented apartments, ran a boarding house (so well described in her book “A House of All Sorts”) and made pottery decorated with motifs derived from Indigenous arts. The discovery of her paintings by Marius Barbeau and Eric Brown, director of the National Gallery of Canada, in 1927 and the inclusion of her paintings in the ground‒breaking “Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art Native and Modern” at the National Gallery that December marked a turning point in her career.

Among the 45 oils and 20 watercolours Carr sent to Ottawa in September 1927 was the canvas she titled “The Bear and Moon Totem, Kispiox”. Barbeau was involved in the organization of the exhibition and possibly it was he who retitled it “Kispsayaks Totem Poles” for the exhibition’s catalogue. He purchased the painting from Carr and reproduced it as “The Totem Pole of the Bear and the Moon” at Kispayaks‒the ‘Hiding Place’ in his novel “The Downfall of Temleham”, published in 1928. The expanded title folded the painting into his romantic retelling of the story of Kamalmuk or Kitwancool Jim and his murder by the white authorities. The Canadian National Railways had subsidized the colour reproductions in Barbeau’s book and thus obtained the rights to reproduce it in its own publicity in 1931. It retained the title “The Totem Pole of the Bear and the Moon, Kispayaks” even though Barbeau had identified it correctly as “Grizzly‒of‒the‒Sun pole” in “Totem Poles of the Gitksan, Upper Skeena River, British Columbia”, published in 1929. When Barbeau loaned it to the exhibition Paintings in Ottawa Collections in 1959, he completed the submission label (still on the back of the painting) as “The Grizzly Bear totem pole of the Upper Skeena, B.C.”

Emily Carr’s misidentification has had a long life, no doubt due to the importance of the painting. Its extensive publication and exhibition history and its association with Marius Barbeau, all add to the reputation of the canvas. The boldly coloured Grizzly totem contrasts with the apparently unpainted pole at the left. The vertical format creates an intimacy that is enhanced by the figures between the poles. The forms are clear, the narrative evocative. Of Carr’s six oil paintings of Ans’pa yaxw resultant from the 1912 trip, Gerta Moray has praised this painting as “Carr’s most successful painting of an individual Gitxsan pole.”

We extend our thanks to Charles Hill, Canadian art historian, former Curator of Canadian Art at the National Gallery of Canada and author of “The Group of Seven‒Art for a Nation”, for his assistance in researching this artwork and for contributing the preceding essay.

“To The Totem Forests: Emily Carr and Contemporaries Interpret Coastal Villages” is an exhibition that incorporates historical photographs to provide new insights into the depiction of Northwest Coast monumental sculpture during the first three decades of the 20th century. A historical photograph of Kispiox relates to Emily Carr “The Totem of the Bear and the Moon”.

The value garnered for this masterpiece by Carr is the twenty-second highest value of any Canadian work of art sold at auction. An incredible result for this celebrated Canadian artist.

Share this item with your friends

Emily Carr

(1871 - 1945) Canadian Group of Painters

Born in Victoria, B.C. She was educated there until she was 16. Her parents died before she was 14 and her eldest sister managed the home. Rebellious against her sister's authority she persuaded the family guardian to allow her to study art in San Francisco. About 1888 she went to the San Francisco School of Art and returned to Victoria about 1895 where she set up a studio in a renovated barn behind her home. There she painted and taught art. In 1897 she travelled to Ucluelet on Vancouver Island, with a missionary friend, where she sketched an Indian village for the first time, but not consciously seeking Indigenous motifs. In her autobiography she wrote, "...to paint the Western forest did not occur to me...I nibbled at silhouetted edges...Unknowingly I was storing...my working ideas against the time when I should be ready to use material."

In Victoria, she had saved enough money through teaching to study in England at the Westminster School of Art, and landscape under Julius Olsson at St. Ives, and landscape under John Whitely at the Meadows Studio, Bushey. Visiting London she took ill and spent 18 months convalescing at the East Anglia Sanatorium which prompted her book "Pause". She returned to Victoria in 1904 and was invited to Vancouver to supervise classes of the Ladies' Art Club of Vancouver. Too serious in her teaching and too unsophisticated for the members' liking, Emily was dismissed after a month. She conducted classes for children in Vancouver which were successful. This brought the Ladies' Art Club President to suggest amalgamation of the two groups, but Emily, understandably, refused. That summer she took a pleasure trip to Alaska with her sister and while she was sketching in Sitka, an American artist seeing her work encouraged her to pursue the Indigenous motif in her own style. It was after this trip that she decided to paint totem poles in their natural settings. Each summer she returned to the Northern coast of B.C. And did many canvases during that five year period (c. 1905-1910). In 1910 having saved enough money to go abroad, she studied in France at the Colorossi where criticisms were given only in French; finding this too difficult to follow she changed to another studio but took ill and travelled to Sweden for a rest. Returning to France a few months later she studied under Harry Gibb both at Cressey-en-Bri and at Brittany. Gibb encouraged individuality and originality in her work and two of her canvases were hung in the Salon d'Automne. Her work gained brightness characteristic of the Fauves which Gibb himself followed. She studied briefly under an "Australian" woman water colourist at Concarneau, later thought to be New Zealand artist Frances Hodgkins by D.W. Buchanan.

She returned to Victoria and to Vancouver in 1912 where she held an exhibition of her French paintings. They were rejected by everyone. Her new style lost her teaching opportunities but her spirit at this point was not broken for she wrote, "In spite of all the insult and scorn shown to my new work I was not ashamed of it...it had brighter, cleaner colour, simpler form, more intensity." With so few pupils she spent more time painting large canvases from her earlier Indigenous village sketches. Finally in 1913 with no pupils, no market for her work, she was forced to return to Victoria. She built an apartment house (The House of All Sorts) from family land and borrowed money. She took in roomers but was not able to make ends meet. In that period she raised 350 Old English Bobtail Sheep-dogs and with her own crude kiln in her back yard made pottery, sometimes in batches of 500 pieces which she decorated with Indigenous designs. These were very much sought after by tourists. She wrote, "...I ornamented my pottery with Indian designs- that was why the tourists bought it...Because my stuff sold, other potters followed my lead and, knowing nothing of Indian Art, falsified it. This made me very angry. I loved handling the smooth clay. I loved the beautiful Indian designs, but I was not happy about using Indian design on material for which it was not intended..."

Running a rooming house, raising dogs, and making pottery kept Emily from painting for about 15 years. It was not until Marius Barbeau in 1921 learned of her work from his Indigenous interpreter and brought it to the attention of Eric Brown, National Gallery of Canada Director, (although Mortimer Lamb had also shown interest in her work) that she became known to the rest of Canada. It was Brown who told her of the Group of Seven and F. B. Housser's book "Canadian Art Movement" which she bought and read from cover to cover. She loaned 50 of her paintings for the West Coast Indian Art exhibit organized by the National Gallery in 1927 and her work was well received. Travelling East for the opening, she visited A.Y. Jackson, J.E.H. MacDonald, and Lawren Harris in Toronto having read of their work in Housser's book. Heading West after the opening, she stopped at Toronto again to see Lawren Harris who became the inspiration and motivation in her development as a painter.

A change of style soon followed her visit East, notably with the canvas "Blunden Harbour" which Dr. Hubbard considers her most monumental of this period. Although Harris influenced her, he never tried to mould her; he encouraged her individuality and eventually prompted her to seek liberation from the dominant Indigenous motif in her work. She turned to the forests of B.C. Using oil-on-paper in a powerful spiral like style described by Dr. Hubbard as an expression of "immense fertility of the earth and the irresistible force of nature.” Emily Carr travelled East several times as an invited contributor to the Group of Seven shows and on one occasion visited New York where she viewed works of American artists. By 1943 however, William Colgate notes in his book, "Her recent painting...is characterized by an eccentricity of design and a cloudiness of colour which stand in marked contrast to her earlier work...Whatever the cause, her painting has indubitably suffered because of it." Eleven years later, on reviewing her water colour work, Paul Duval wrote, "She did not hesitate to use whatever means necessary to attain her desired end. Some passages in her painting have a scrubbed look, others are delicately washed in, and there are frequent moments when her brush slashes appear with the marks of a lash. System or no, Emily Carr registered souvenirs of her love of the Pacific Coast which are as affecting as any created in Canada." Emily Carr sold her apartment home in 1936 and turned to full time painting and writing. Through a friend, Ira Dilworth learned of her work and became her literary executive. He had her stories read over the CBC at Vancouver and later took her manuscripts to the Oxford University Press in Toronto. "Klee Wyck" was published in 1941 and won the Governor General's award for the best non-fiction of that year; others followed: "The Book of Small", "The House of All Sorts", "Growing Pains", "The Heart of A Peacock", "Pause-A Sketch Book". Her paintings are in the collections of the following galleries: Art Association of Montreal, Art Gallery of Ontario, Hart House, University of Toronto, Vancouver Art Gallery, The Lord Beaverbrook Collection, and the National Gallery of Canada in addition to many private collections.

Source: "A Dictionary of Canadian Artists, Volume I: A-F", compiled by Colin S. MacDonald, Canadian Paperbacks Publishing Ltd, Ottawa, 1977