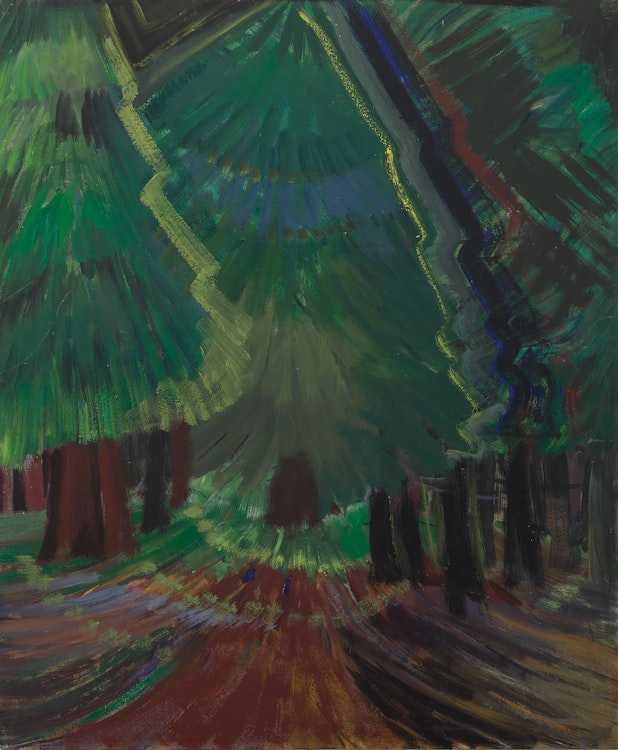

Forest Glade (Dark Glade) by Emily Carr

Emily Carr

Forest Glade (Dark Glade)

oil on paper on board

stamped (twice) along the lower edge; inscribed “Dark Glade” on the reverse of the board; titled “Forest Glade” on the Dominion Gallery label on the reverse (Dominion Gallery Inventory #B176)

28.75 x 23.75 ins ( 73 x 60.3 cms )

Auction Estimate: $100,000.00 - $150,000.00

Price Realized $216,000.00

Sale date: December 3rd 2020

Estate of Emily Carr

Dominion Gallery, Montreal (acquired from the above, per executor Lawren Harris, 1945)

Private Collection, Ottawa (acquired from Dominion Gallery in May, 1954)

Sotheby’s Canada, auction, Toronto, November 26, 1984, lot 53

The Collection of TC Energy, Calgary

Sotheby’s, “Important Canadian Art and Fine Jewellery”, auction catalogue, Toronto, November 26, 1984, reproduced lot 53 (unpaginated) and on the front cover

Emily Carr, “The Complete Writings of Emily Carr”, Toronto/Vancouver, 1993, pages 793-94

Maria Tippet, “Emily Carr: A Biography”, Toronto, 1994, page 238

The foregoing quote, taken from Emily Carr’s journal entry in “A Tabernacle in the Wood” on September 29th, 1935, beautifully illustrates Carr’s approach to the subject. She was deeply in tune with the forest, and as a result, she saw beauty everywhere. “There are themes everywhere, something sublime, something ridiculous, or joyous, or calm, or mysterious. Tender youthfulness laughs at gnarled oldness. Moss and ferns, and leaves and twigs, light and air, depth and colour chattering, dancing a mad joy-dance, but only apparently tied up in stillness and silence. You must be still in order to hear and see.” In the undergrowth, in the forest floor, the red, fecund earth of the woods, Carr found her beauty.

“Forest Glade” comes from the period in Carr’s life when she was working in thinned oil paint on paper. She used oil-based commercial house paint rather than artist’s oils, which she further thinned to the consistency of cream. This allowed her to orchestrate the movement of the paint very quickly, allowing her deep sensitivity to the life-essence forest itself, to its subtle – and not so subtle – quivers and shudders and connectedness to the wind, sunlight, and air, to be instantly captured. It was a mad joy-dance indeed, between a sensitive soul and her fleeting subject, made possible by her adjustments to her media. Her written descriptions of the forest drip with emotive response, and her painted reactions are equally empathic. “How solemn the pines look,” she writes, “more grey than green, a quiet spiritual grey, blatant gaudiness of colours swallowed, only the beautiful carrying power of grey, lifting into mystery. Colour holds, binds, ‘enearths’ you. When light shimmers on colours, folds them round and round, colour is swallowed by glory and becomes unspeakable.” Works from these years – 1937-1942 – are often compared to those of Vincent Van Gogh, “both [are] expressionists, and work, as far as one can judge, under the influence of deep and intense feelings.” Carr’s mastery of atmosphere, colour, and mood were praised, and in these years, she was offered more exhibition opportunities than she could generate work to meet. With failing health and a resulting decreased mobility, she begrudgingly adjusted her methods and focused on working from a central base, with short excursions or a convenient porch as a painting place.

Camping in her beloved van dubbed ‘the elephant,’ or (after 1938) staying in a rented cottage, she would complete her camp chores and then find a place not too far afield, a place just open enough for her to sit and spread out her gear. Then she would wait and let the forest speak to her. She describes her practice in the same journal, from earlier that same September: “Wait. Out comes a cigarette. The mosquitoes back away from the smoke. Everything is green. Everything is waiting and still. Slowly things begin to move, to slip into their places. Groups and masses and lines tie themselves together. Colours you had not noticed come out, timidly or boldly. In and out, in and out your eye passes. Nothing is crowded; there is living space for all... The green is full of colour. Light and dark chase each other. Here is a picture, a complete thought, and there and another and there...”

The charm and intimacy of works from this period are as singular and unique as each small glade she worked within. They are completely honest and uncontrived. In “Forest Glade”, Carr’s broad brushstrokes radiate from the pines themselves, forming a burst of energy that fills the page, radiating outwards past the confines of the work’s dimensions. Here she has captured the very life force of the forest, the essence of its verdant growth and persistent, unrestrainable life. Her compositional energy radiates outwards and upwards from the low centre of the work, where a sunburst of brilliance forms and swoops towards us along the forest floor. This spark lights the most central pine first, then captures the others in its vibrating, radiating outward moving hum.

“Forest Glade” was acquired by Montreal’s Dominion Gallery from the estate of Emily Carr in 1945, as per Carr’s executor, Lawren Harris. The painting was sold by Dominion to an Ottawa collector in May of 1954, eventually arriving in the collection of Calgary’s TC Energy. Uniquely framed in fragrant Canadian cedar, touched with 24 karat gold, “Forest Glade” speaks eloquently to Carr’s deeply-felt connection to the forest of British Columbia and its wild, untamed beauty.

We extend our thanks to Lisa Christensen, Canadian art academic and the author of three award-winning books on Canadian art, for contributing the preceding essay.

We extend our thanks to Charles Hill, Canadian art historian, former Curator of Canadian Art with the National Gallery of Canada and author of “The Group of Seven - Art for a Nation”, for his assistance in researching the provenance of this artwork.

Share this item with your friends

Emily Carr

(1871 - 1945) Canadian Group of Painters

Born in Victoria, B.C. She was educated there until she was 16. Her parents died before she was 14 and her eldest sister managed the home. Rebellious against her sister's authority she persuaded the family guardian to allow her to study art in San Francisco. About 1888 she went to the San Francisco School of Art and returned to Victoria about 1895 where she set up a studio in a renovated barn behind her home. There she painted and taught art. In 1897 she travelled to Ucluelet on Vancouver Island, with a missionary friend, where she sketched an Indian village for the first time, but not consciously seeking Indigenous motifs. In her autobiography she wrote, "...to paint the Western forest did not occur to me...I nibbled at silhouetted edges...Unknowingly I was storing...my working ideas against the time when I should be ready to use material."

In Victoria, she had saved enough money through teaching to study in England at the Westminster School of Art, and landscape under Julius Olsson at St. Ives, and landscape under John Whitely at the Meadows Studio, Bushey. Visiting London she took ill and spent 18 months convalescing at the East Anglia Sanatorium which prompted her book "Pause". She returned to Victoria in 1904 and was invited to Vancouver to supervise classes of the Ladies' Art Club of Vancouver. Too serious in her teaching and too unsophisticated for the members' liking, Emily was dismissed after a month. She conducted classes for children in Vancouver which were successful. This brought the Ladies' Art Club President to suggest amalgamation of the two groups, but Emily, understandably, refused. That summer she took a pleasure trip to Alaska with her sister and while she was sketching in Sitka, an American artist seeing her work encouraged her to pursue the Indigenous motif in her own style. It was after this trip that she decided to paint totem poles in their natural settings. Each summer she returned to the Northern coast of B.C. And did many canvases during that five year period (c. 1905-1910). In 1910 having saved enough money to go abroad, she studied in France at the Colorossi where criticisms were given only in French; finding this too difficult to follow she changed to another studio but took ill and travelled to Sweden for a rest. Returning to France a few months later she studied under Harry Gibb both at Cressey-en-Bri and at Brittany. Gibb encouraged individuality and originality in her work and two of her canvases were hung in the Salon d'Automne. Her work gained brightness characteristic of the Fauves which Gibb himself followed. She studied briefly under an "Australian" woman water colourist at Concarneau, later thought to be New Zealand artist Frances Hodgkins by D.W. Buchanan.

She returned to Victoria and to Vancouver in 1912 where she held an exhibition of her French paintings. They were rejected by everyone. Her new style lost her teaching opportunities but her spirit at this point was not broken for she wrote, "In spite of all the insult and scorn shown to my new work I was not ashamed of it...it had brighter, cleaner colour, simpler form, more intensity." With so few pupils she spent more time painting large canvases from her earlier Indigenous village sketches. Finally in 1913 with no pupils, no market for her work, she was forced to return to Victoria. She built an apartment house (The House of All Sorts) from family land and borrowed money. She took in roomers but was not able to make ends meet. In that period she raised 350 Old English Bobtail Sheep-dogs and with her own crude kiln in her back yard made pottery, sometimes in batches of 500 pieces which she decorated with Indigenous designs. These were very much sought after by tourists. She wrote, "...I ornamented my pottery with Indian designs- that was why the tourists bought it...Because my stuff sold, other potters followed my lead and, knowing nothing of Indian Art, falsified it. This made me very angry. I loved handling the smooth clay. I loved the beautiful Indian designs, but I was not happy about using Indian design on material for which it was not intended..."

Running a rooming house, raising dogs, and making pottery kept Emily from painting for about 15 years. It was not until Marius Barbeau in 1921 learned of her work from his Indigenous interpreter and brought it to the attention of Eric Brown, National Gallery of Canada Director, (although Mortimer Lamb had also shown interest in her work) that she became known to the rest of Canada. It was Brown who told her of the Group of Seven and F. B. Housser's book "Canadian Art Movement" which she bought and read from cover to cover. She loaned 50 of her paintings for the West Coast Indian Art exhibit organized by the National Gallery in 1927 and her work was well received. Travelling East for the opening, she visited A.Y. Jackson, J.E.H. MacDonald, and Lawren Harris in Toronto having read of their work in Housser's book. Heading West after the opening, she stopped at Toronto again to see Lawren Harris who became the inspiration and motivation in her development as a painter.

A change of style soon followed her visit East, notably with the canvas "Blunden Harbour" which Dr. Hubbard considers her most monumental of this period. Although Harris influenced her, he never tried to mould her; he encouraged her individuality and eventually prompted her to seek liberation from the dominant Indigenous motif in her work. She turned to the forests of B.C. Using oil-on-paper in a powerful spiral like style described by Dr. Hubbard as an expression of "immense fertility of the earth and the irresistible force of nature.” Emily Carr travelled East several times as an invited contributor to the Group of Seven shows and on one occasion visited New York where she viewed works of American artists. By 1943 however, William Colgate notes in his book, "Her recent painting...is characterized by an eccentricity of design and a cloudiness of colour which stand in marked contrast to her earlier work...Whatever the cause, her painting has indubitably suffered because of it." Eleven years later, on reviewing her water colour work, Paul Duval wrote, "She did not hesitate to use whatever means necessary to attain her desired end. Some passages in her painting have a scrubbed look, others are delicately washed in, and there are frequent moments when her brush slashes appear with the marks of a lash. System or no, Emily Carr registered souvenirs of her love of the Pacific Coast which are as affecting as any created in Canada." Emily Carr sold her apartment home in 1936 and turned to full time painting and writing. Through a friend, Ira Dilworth learned of her work and became her literary executive. He had her stories read over the CBC at Vancouver and later took her manuscripts to the Oxford University Press in Toronto. "Klee Wyck" was published in 1941 and won the Governor General's award for the best non-fiction of that year; others followed: "The Book of Small", "The House of All Sorts", "Growing Pains", "The Heart of A Peacock", "Pause-A Sketch Book". Her paintings are in the collections of the following galleries: Art Association of Montreal, Art Gallery of Ontario, Hart House, University of Toronto, Vancouver Art Gallery, The Lord Beaverbrook Collection, and the National Gallery of Canada in addition to many private collections.

Source: "A Dictionary of Canadian Artists, Volume I: A-F", compiled by Colin S. MacDonald, Canadian Paperbacks Publishing Ltd, Ottawa, 1977